Eb White Art of an Essay Paris Review Fall 1969

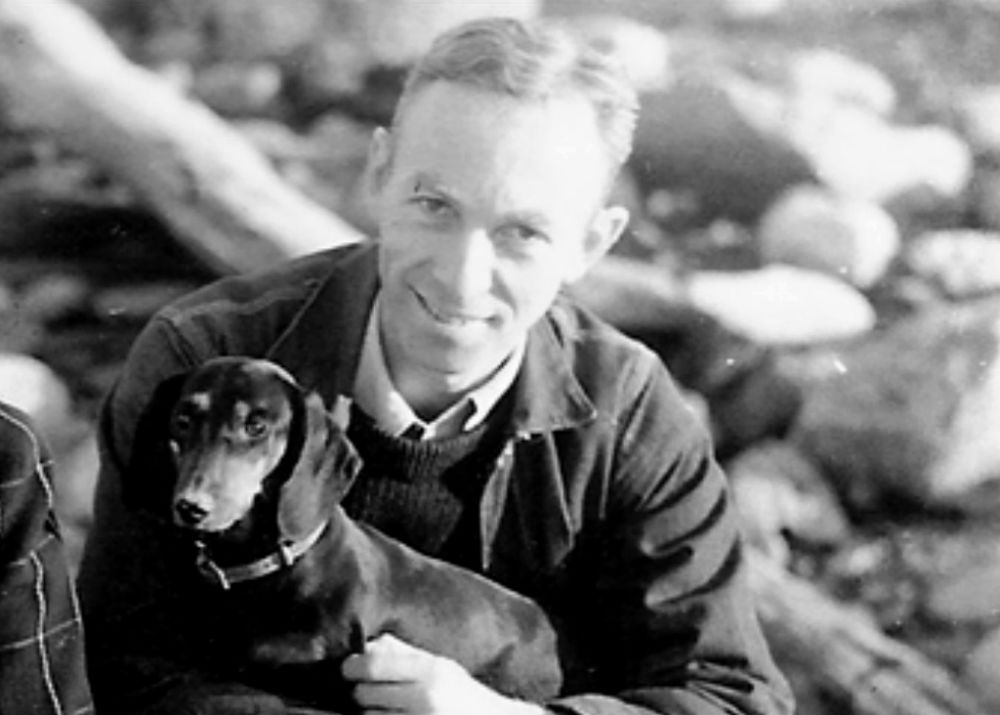

E. B. White and his dog Minnie.

E. B. White and his dog Minnie.

If it happens that your parents business organization themselves and so piffling with the workings of boys' minds as to christen you Elwyn Brooks White, no dubiety you lot decide equally early equally possible to identify yourself as E.B. White. If information technology also happens that yous nourish Cornell, whose first president was Andrew D. White, and then, following a variant of the principle that everybody named Rhodes winds up being nicknamed "Dusty," you lot current of air up being nicknamed "Andy." And so it has come well-nigh that for fifty of his seventy years Elwyn Brooks White has been known to his readers as E.B. White and to his friends as Andy. Andy White. Andy and Katharine White. The Whites. Andy and Katharine have been married for forty years, and in that time they have been separated so rarely that I discover information technology impossible to think of one without the other. On the occasions when they have been obliged to be autonomously, Andy'southward conversation is so likely to center on Katharine that she becomes all the more present for existence absent.

The Whites have shared everything, from professional association on the same mag to preoccupation with a articulation sick health that many of their friends have been inclined to regard as imaginary. Years ago, in a Christmas doggerel, Edmund Wilson saluted them for possessing "mens sana in corpore insano," and it was always wonderful to behold the intuitive seesaw adjustments by which i of them got well in time for the other to go ill. What a mountain of expert work they have accumulated in that fashion! Certainly they have been the strongest and most productive unhealthy couple that I have always encountered, but I no longer dare to make fun of their ailments. At present that age is bestowing on them a natural infirmity, they must be sorely tempted to say to the rest of us, "Y'all encounter? What did we tell y'all?" ("Sorely," by the way, has been a favorite adverb of Andy'southward- a word that brims with bodily woe and that yet hints at the heroic: back of Andy, some dying knight out of Malory lifts his gleaming sword against the dusk.)

Andy White is small and wiry, with an unexpectedly large nose, speckled eyes, and an air of being only near to plow away, non on an errand of any importance just every bit a means of remaining gratis to cut and run without the nuisance of prolonged good-byes. Crossing the threshold of his eighth decade, his person is uncannily boyish-seeming. Though his hair is greyness, I larn at this moment that I do not consent to the fact: away from him, I recollect information technology as brown, therefore it is brown to me. Andy tin no more lose his youthfulness by the boring blow of growing old than he could ever have been Elwyn by the tiresome united nations-necessary blow of baptism; his youth and his "Andy"-ness are intrinsic and inexpungeable. Katharine White is a woman so expert-looking that nobody has taken it amiss when her hubby has described in print as cute, but her beauty has a touch of blue-eyed augustness in it, and her manner is formal. It would never occur to me to get beyond calling her Katharine, and I have not found it surprising when her son, Roger Angell, an editor ofThe New Yorker, refers to her within the part precincts equally "Mrs. White." (Roger Angell is the son of her matrimony to a distinguished New York attorney, Ernest Angell; she and Andy have a son, Joe, who is a naval architect and whose boatyard is a thriving enterprise in the Whites' hometown of Brooklin, Maine.)

At the gamble of reducing a man'south life to a sort of Merck's Manual, I may mention that Andy White's personal physician, Dana Atchley- giving characteristically short shrift to a psychosomatic view of his erstwhile friend- has described him as having a Rolls Royce listen in a Model T body. With Andy, this would pass for a compliment, considering in the tyranny of his modesty he would always choose to be a Ford instead of a Rolls, but it would be closer to the truth to draw him as a Rolls Royce mind in a Rolls Royce trunk that unaccountably keeps bumping to a end and humming to itself, not without infinite pleasure to others along the way. What he achieves must cost him a considerable effort and appears to cost him very footling. His speaking voice, like his writing vocalization, is clear, resonant, and invincibly debonair. He wanders over the pastures of his Maine farm or, for that matter, along the labyrinthine corridors ofThe New Yorker offices on West Xl-Third Street with the off-mitt grace of a dancer making up a sequence of steps that the middle follows with delight and that defies whatsoever but his own notation. Clues to the bold and delicate nature of those steps are to be discovered in every line he writes, but the human and his piece of work are so near one that, endeavor every bit we will, we cannot tell the dancer from the dance.

-Brendan Gill

INTERVIEWER

So many critics equate the success of a writer with an unhappy childhood. Can you say something of your ain childhood in Mount Vernon?

E.B. WHITE

Every bit a kid, I was frightened merely not unhappy. My parents were loving and kind. We were a large family unit (six children) and were a small-scale kingdom unto ourselves. Nobody ever came to dinner. My father was formal, conservative, successful, hardworking, and worried. My mother was loving, hardworking, and retiring. Nosotros lived in a large house in a leafy suburb, where at that place were backyards and stables and grape arbors. I lacked for nothing except conviction. I suffered aught except the routine terrors of childhood: fear of the dark, fear of the future, fearfulness of the render to school afterward a summer on a lake in Maine, fear of making an appearance on a platform, fear of the lavatory in the school basement where the slate urinals cascaded, fear that I was unknowing about things I should know almost. I was, as a child, allergic to pollens and dusts, and still am. I was allergic to platforms, and all the same am. Information technology may be, every bit some critics propose, that it helps to have an unhappy childhood. If so, I have no knowledge of it. Perhaps it helps to have been scared or allergic to pollens—I don't know.

INTERVIEWER

At what age did you know you were going to follow a literary profession? Was there a particular incident, or moment?

WHITE

I never knew for sure that I would follow a literary profession. I was 20-seven or xx-eight before anything happened that gave me any assurance that I could make a go of writing. I haddone a swell deal of writing, only I lacked confidence in my ability to put it to practiced apply. I went abroad one summer and on my render to New York found an aggregating of mail at my apartment. I took the letters, unopened, and went to a Childs eating place on Fourteenth Street, where I ordered dinner and began opening my mail. From i envelope, two or 3 checks dropped out, fromThe New Yorker. I suppose they totaled a little under a hundred dollars, but it looked like a fortune to me. I can still call back the feeling that "this was it"—I was a pro at concluding. It was a good feeling and I enjoyed the meal.

INTERVIEWER

What were those offset pieces accepted pastThe New Yorker? Did you transport them in with a covering letter, or through an amanuensis?

WHITE

They were short sketches—what Ross chosen "casuals." Ane, I think, was a piece chosen "The Swell Steerage," about the then new higher cabin form on transatlantic ships. I never submitted a manuscript with a covering letter of the alphabet or through an agent. I used to put my manuscript in the mail, along with a stamped envelope for the rejection. This was a affair of high principle with me: I believed in the doctrine of immaculate rejection. I never used an agent and did not similar the looks of a manuscript afterward an amanuensis got through prettying it up and putting it between covers with brass clips. (I now have an agent for such mysteries as picture rights and foreign translations.)

A large part of all early contributions toThe New Yorker arrived uninvited and unexpected. They arrived in the mail or under the arm of people who walked in with them. O'Hara'southward "Afternoon Delphians" is one example out of hundreds. For a number of years,The New Yorker published an average of fifty new writers a year. Magazines that decline unsolicited manuscripts strike me equally lazy, incurious, cocky-assured, and self-of import. I'thousand speaking of magazines of general circulation. There may exist some justification for a technical journal to limit its listing of contributors to persons who are known to be qualified. But if I were a publisher, I wouldn't want to put out a magazine that failed to examine everything that turned upwards.

INTERVIEWER

But didThe New Yorker always endeavor to publish the emerging writers of the time: Hemingway, Faulkner, Dos Passos, Fitzgerald, Miller, Lawrence, Joyce, Wolfe, et al?

WHITE

The New Yorker had an involvement in publishing whatever author that could turn in a good piece. It read everything submitted. Hemingway, Faulkner, and the others were well established and well paid whenThe New Yorker came on the scene. The magazine would have been glad to publish them, just information technology didn't have the coin to pay them off, and for the most part they didn't submit. They were selling toThe Saturday Evening Post and other well-heeled publications, and in general were non inclined to contribute to the small-scale, new, impecunious weekly. Too, some of them, I would gauge, did non feel sympathetic toThe New Yorker's frivolity. Ross had no great urge to publish the large names; he was far more interested in turning upwards new and yet undiscovered talent, the Helen Hokinsons and the James Thurbers. We did publish some things by Wolfe—"Only the Dead Know Brooklyn" was one. I believe we published something past Fitzgerald. Just Ross didn't waste matter much time trying to corral "emerged" writers. He was looking for the ones that were plant by turning over a stone.

INTERVIEWER

What were the procedures in turning downwardly a manuscript by aNew Yorker regular? Was this done past Ross?

WHITE

The manuscript of aNew Yorker regular was turned down in the same way as was the manuscript of aNew Yorker irregular. Information technology was simply rejected, usually past the subeditor who was treatment the author in question. Ross did not deal directly with writers and artists, except in the case of a few old friends from an earlier day. He wouldn't even accept on Woollcott—regarded him as likewise hard and fussy. Ross disliked rejecting pieces, and he disliked firing people—he ducked both tasks whenever he could.

INTERVIEWER

Did feuds threaten the mag?

WHITE

Feuds did non threatenThe New Yorker. The only feud I recall was the running battle between the editorial section and the advertising department. This was largely a ane-sided affair, with the editorial department lobbing an occasional grenade into the enemy's lines just on full general principles, to assistance them recall to stay out of sight. Ross was determined non to allow his magazine to be swayed, in the slightest degree, by the boys in advertising. As far every bit I know, he succeeded.

INTERVIEWER

When did you lot first move to New York, and what were some of the things you did before joiningThe New Yorker? Were y'all ever a part of the Algonquin grouping?

WHITE

After I got out of higher, in 1921, I went to piece of work in New York only did non live in New York. I lived at abode, with my father and female parent in Mount Vernon, and commuted to work. I held three jobs in nearly 7 months—first with the United Press, then with a public relations man named Wheat, then with the American Legion News Service. I disliked them all, and in the bound of 1922 I headed west in a Model T Ford with a college mate, Howard Cushman, to seek my fortune and as a fashion of getting away from what I disliked. I landed in Seattle half dozen months afterwards, worked there as a reporter on theTimes for a yr, was fired, shipped to Alaska aboard a freighter, and so returned to New York. It was on my return that I became an advertisement man—Frank Seaman & Co., J. H. Newmark. In the mid-twenties, I moved into a ii-room apartment at 112 West Thirteenth Street with iii other fellows, college mates of mine at Cornell: Burke Dowling Adams, Gustave Stubbs Lobrano, and Mitchell T. Galbreath. The hire was $110 a calendar month. Split 4 means it came to $27.l, which I could afford. My friends in those days were the fellows already mentioned. Also, Peter Vischer, Russell Lord, Joel Sayre, Frank Sullivan (he was older and more advanced simply I met him and liked him), James Thurber, and others. I was never a part of the Algonquin group. Afterwards becoming connected withThe New Yorker, I lunched once at the Circular Tabular array but didn't care for it and was embarrassed in the presence of the great. I never was well acquainted with Benchley or Broun or Dorothy Parker or Woollcott. I did not know Don Marquis or Band Lardner, both of whom I profoundly admired. I was a younger man.

douglasalaire1937.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4155/the-art-of-the-essay-no-1-e-b-white

0 Response to "Eb White Art of an Essay Paris Review Fall 1969"

Post a Comment